In my last post, I talked about how, one hundred years ago, diamondback terrapins were almost eaten to extinction because people back then really liked diamondback terrapin stew.

Even though today you are unlikely to ever see a diamondback terrapin stew food truck or McDiamondback Terrapin Stew on the menu board at McDonalds, diamondback terrapins are still not doing great. One of the problems diamondback terrapins continue to face is habitat loss. People like to build things like houses and seafood restaurants and roads right on or right next to salt marshes.

Building around salt marshes takes away habitat and nesting sites from diamondback terrapins, makes them more likely to be run over by cars and creates pollution that gets into the marsh waters where they live.

Though habitat loss is not helping diamondback terrapins at all, the bigger problem for diamondback terrapins today, at least in states like Maryland and South Carolina, is crab traps. You heard me.

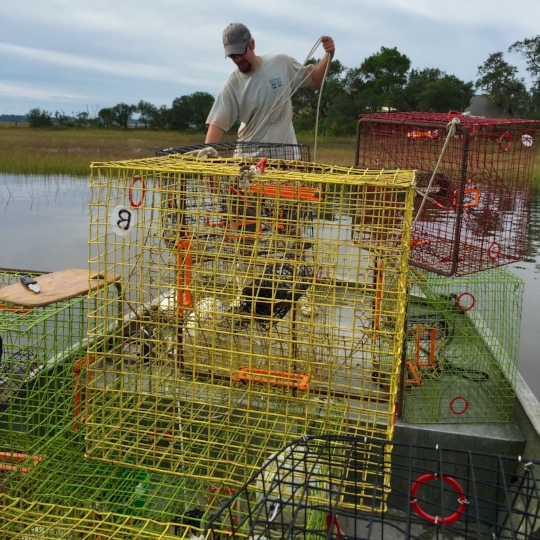

Crab traps are traps that look like this:

Crab traps aren’t traps to catch grumpy people. Crab traps catch grumpy crabs. If you look at this photo, and can ignore that the trap appears to have a face, you can see there is an unhappy blue crab in the left corner of this trap (this kind of trap is actually called a crabpot). On the East Coast of the United States, people use traps like this to catch blue crabs in salt marshes and estuaries, because people on the East Coast of the United States really like to eat blue crabs as crab cakes, she-crab soup and soft shell crab.

Here’s what a blue crab looks like before it becomes a crab cake.

Blue crabs are opportunistic scavengers, meaning if there is the opportunity to eat something dead, then a blue crab is probably going to take it. Blue crab fisherpeople catch blue crabs by putting chunks of dead meat, like pieces of raw chicken, fish or clams, inside the trap. The trap is then thrown into the water, like this:

The white float you see attached to the trap sits on the surface of the water and helps the fisherperson find the trap again. It also warns boaters, “There’s a crab trap here and you probably don’t want to hit it with your propeller because that will not be good for anyone.” (Despite the fact that I just put that in quotes, the crab trap floats do not actually say that out loud. It’s more implied).

Once the trap is in the water, blue crabs can smell the dead stuff inside it and will look for a way to enter the trap so they can eat some raw dead meat. A crab trap has openings (if you look at the photo of the crabpot again, the openings are the parts that looks like a mouth with orange lipstick). The openings allow blue crabs to get inside the trap. Once the crab is in the trap, it is really difficult for the crab to get back out. (You can learn more about how a crabpot keeps crabs inside the trap here.)

As you can see in this video of a blue crab inside a much simpler crab trap than a crabpot, a blue crab basically just chills in a trap, and may even enjoy a snack or, if the trap has a GoPro inside it, take selfies…

…until the fisherman collects the trap, and then its life becomes stressful.

The problem for diamondback terrapins is the bait in blue crab traps also attracts diamondback terrapins. Diamondback terrapins like to eat live animals like periwinkle snails and fiddler crabs, but they are also happy to eat dead stuff. Diamondback terrapins will enter blue crab traps to try to eat the dead stuff inside, but once they are inside the trap, they can’t get out either. Crab traps may be left underwater for hours before the fisherpeople collect them to see what they caught. Diamondback terrapins breathe with lungs, so, if they are underwater that long, they will drown. This happens often enough that crab traps are currently the #1 cause of death in diamondback terrapins.

Scientists realized crab traps were a problem for diamondback terrapins in the 1990s. After that, someone had the idea that we could help diamondback terrapins by using TEDs. This TED acronym has nothing to do with talks about Technology, Entertainment and Design. The crab trap TED acronym stands for Turtle Excluder Device. (By the way, I did a search and apparently no one has done a TED Talk about TEDs).

Diamondback terrapin TEDs are plastic contraptions that are attached to blue crab trap openings.

The orange plastic thing on this crab pot is a TED (Turtle Excluder Device). This was a TED design the scientists used in 2014.

TEDs make the openings in the trap smaller so it is harder or hopefully impossible for a diamondback terrapin to enter the trap, but still easy for a blue crab. TEDs are effective enough that in some states, like Maryland, people who use blue crab traps are required by law to install TEDs on their traps. In other states, like South Carolina, blue crab fisherpeople can use TEDs, but only if they want to.

To get blue crab fisherpeople to voluntarily use TEDs, it is necessary to show them that TEDs can save diamondback terrapins without causing the crab trap to catch fewer blue crabs. Biologists at the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Marine Resources Research Institute have been collecting data to solve this problem for a few years now. One day while I was visiting South Carolina, I was able to help them with this research project.

The day I volunteered, I went out to a salt marsh tidal creek for about eight hours with the wildlife biologists Ellen Waldrop and Jeff Schwenter.

Ellen Waldrop and Jeff Schwenter

We traveled in a small boat and brought sixteen crab traps with us.

The sixteen crab traps consisted of four sets of traps with four crab traps each. Each set had three traps with TEDs on them, though each of those three traps had a different kind of TED with different sized openings. The trap without a TED was the control (if you’re not sure what a scientific control is, read this).

Each set of traps was put in the water at a predetermined site on the tidal creek. (That’s what Jeff is doing in those photos I pasted above where he is flinging a crab trap into the water).

If you look closely you can see the white floats on the water that are attached to crab traps we deployed

After the traps sat out in the water for a little while, we collected them to see what each trap with its different opening had caught.

We did not catch any diamondback terrapins that day, but we did catch lots of blue crabs. We counted how many blue crabs were in each trap. We also carefully measured each crab.

Measurements would let us know exactly how big the crabs were in each trap. Blue crab fishermen generally prefer to catch bigger crabs. If the data showed that a certain kind of TED was only letting in tiny crabs, then blue crab fishermen would probably be less likely to use it.

The measurement data about the crabs was carefully recorded for each trap, along with the trap’s location in the salt marsh, the times the trap entered and left the water, and what the tides were like during that time.

Once all the data was recorded, we released the blue crabs back into the water. Before we did this, though, we painted them with nail polish. This was not because we wanted to make up for giving them a stressful experience by giving them a manicure. The nail polish is a nontoxic, waterproof way to mark the crabs. Each of them was given a dot on its back. That way the scientists could easily see if they were getting any repeat customers in their crab traps.

These fashionable crabs are wearing dabs of red nail polish.

Here I am releasing some crabs.

If the results of this entire project were based on our one day of data, then we could say that all three TED designs keep out diamondback terrapins and traps without TEDs keep out diamondback terrapins too, because we did not catch any diamondback terrapins. But that would be inaccurate, because there have been many instances seen by crab fisherpeople and scientists of diamondback terrapins being caught in crab traps. Ellen and Jeff and the other scientists on this project did not stop collecting data after one day, because all scientists know they have to collect lots and lots of data to find the best answers to their questions. During 2014 and 2015 the scientists on this project went out in the field to collect data almost 100 days, for a total of about 3100 hours. They put traps in the water over 700 times. By doing this over and over again they were able to collect a lot of data about which TED designs were best at keeping out diamondback turtles while letting in blue crabs.

So far, the data has shown that the width of the TED opening matters more than the height of the TED openings to keep diamondback terrapins out. This data has already been used to design a better TED, that you can see in action below.

This new TED design has been working so well that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has purchased a bunch of them to give out to crab fisherpeople.

You can learn about how the scientists came up with this new TED design here.

But the project hasn’t ended. This year they are putting crab traps in the water with underwater cameras so they can film what is happening when blue crabs try to enter a crab trap and then give up because of a TED. These videos may show what about the TEDs keeps the crabs from entering the trap. This data may help the scientists come up with even better designs that will allow more blue crabs to enter a trap, which will make blue crab fisherpeople more likely to use TEDs.

This research project shows how science can help to create a win-win situation for wildlife and people. By testing TED designs, the scientists can find the best TED to prevent diamondback terrapins from drowning, while also allowing blue crab fisherpeople to catch enough blue crabs to make a living.

As someone who loves science, it's exciting when I get to work with real scientists and I am grateful to Ellen Waldrop, Jeff Schwenter, and Mike Arendt for allowing me to have the experience!

2018 update:

The scientists who did this research have now published their findings. You can read about what they have learned here.

To learn more about diamondback terrapins, blue crabs and salt marshes, read my book A Day in the Salt Marsh.

Online References and Resources:

Blue Crab Info. "Crabbing for Hard Shell Crabs,"

http://wetlandsinstitute.org/conservation/terrapin-conservation/terrapins-and-traps/

Diamondback Terrapin Working Group. "Research Bibliography."

http://www.dtwg.org/Bibliography.htm

Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Diamondback Terrapin TED brochure.

http://dnr2.maryland.gov/Wildlife/documents/terrapinbrochure.pdf

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. "Diamondback Terrapin."

http://www.dnr.sc.gov/wildlife/diamondbackterrapin/

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. "Diamondback Terrapin Research - Fisheries Interactions and Bycatch Reduction"

http://www.dnr.sc.gov/wildlife/diamondbackterrapin/research/fisheries.html

Wetlands Institute. "Terrapins and Traps."

http://wetlandsinstitute.org/conservation/terrapin-conservation/terrapins-and-traps/

Photos and Images:

Click the photos and images used above to find their sources. If the photo does not link anywhere, it was taken by Kevin Kurtz, unless, of course, it has Kevin Kurtz in it. Then it was taken by Jeff Schwenter.