If you have been sick lately, then chances are you had uninvited guests inside you. You can figure out which uninvited guests crashed your body by naming your sickness. If you had, say, Lyme disease, anthrax, or botulism, then your uninvited guests were some kind of bacteria. If you had the cold, the flu, chicken pox, or rabies, then your uninvited guests were viruses.

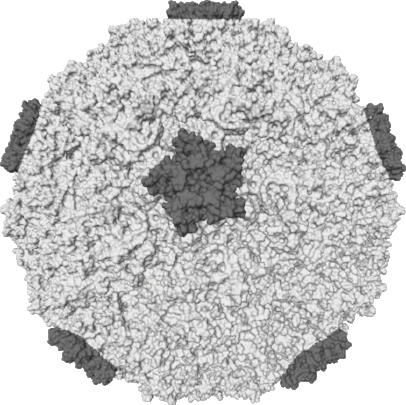

Even though this looks kind of like a latch hook rug of a soccer ball, it is a computer-generated image of one of the viruses that give us colds. This type is called a rhinovirus. It does not have that name because it will turn you into a rhinoceros (though that would be awesome). "Rhino" is the Greek word for nose. Cold viruses basically take over your nose, so they are called "rhinoviruses."

So, if you happen to have this rug in your bedroom, tell your friends it is a latch hook rug of a rhinovirus.

Bacteria and viruses are both microscopic in size. At least some viruses and bacteria invade living things and cause diseases. Beyond that, though, bacteria and viruses don’t have a lot in common. For one thing, one of them is a living thing. The other one breaks almost all of the rules of what makes something a living thing.

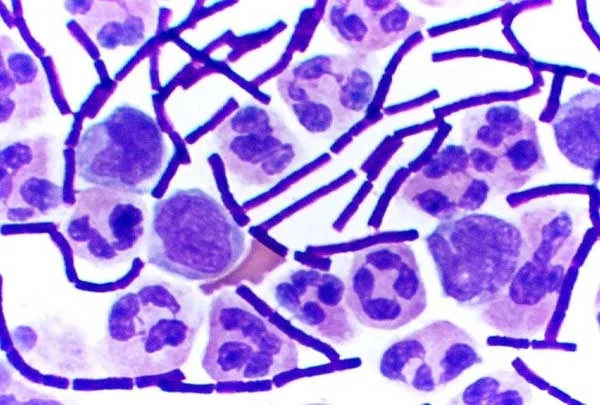

Bacteria are definitely living things. Like us, they need water, energy, and nutrients from their environment in order to keep their bodies going (We call the activity inside a living thing’s body that keeps it going its metabolism.). Like us, bacteria grow during their lifetime. They also reproduce, but not the way we do, because no person splits in two to form an exact replica of themselves, except in some comic books I have read. Bacteria split in two to make new bacteria all the time.

Viruses don’t need water, energy, or nutrients to keep their metabolism going, because they don’t have a metabolism. Without a metabolism, they can’t grow. They also can potentially be around forever because they don’t have a metabolism to stop, which means they don’t die in the same way living things do. Also, viruses can’t reproduce by splitting apart or having babies or laying eggs or making spores or seeds or any other way that living things reproduce.

So in this checklist of characteristics I included in my book Living Things and Nonliving Things to figure out if something is a living thing or not:

Breathe.

Drink water.

Take energy and nutrients from its environment.

Reproduce

Grow and Change.

Viruses don’t do any of those things (with one exception, kind of).

And that’s not all. Living things tend to have complex structures. This means each living thing has a lot of different parts that do different things. All the parts have to work together to keep the organism alive. This is true of even single-celled bacteria. A bacterium’s cell has different parts with names like fimbriae, ribosomes, and vacuoles (“Fimbriae” sounds like it could be the name of some kid born in the 21st Century. Please don’t ever name a kid “Vacuole,” though. I foresee terrible nicknames in that kid’s future). These parts work together to keep the bacterium alive.

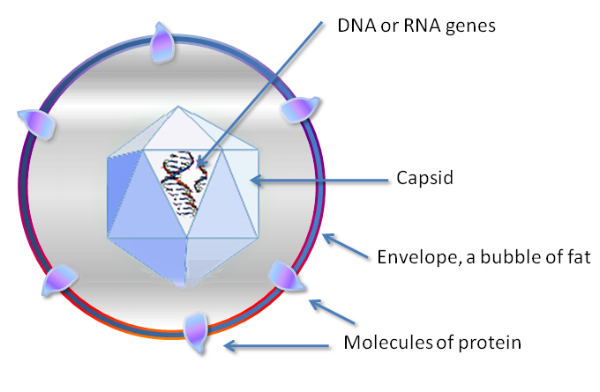

A virus is not complex. It is basically just DNA in a box (though the box is made of protein and not cardboard).

With all those things against it, most scientists agree viruses aren’t living things. But some scientists argue that viruses should be considered living things.

There are a few reasons it’s easy to be wishy-washy about the living thing status of viruses.

The bodies of viruses pretty much have nothing in common with living things, except they contain DNA. DNA molecules are teeny-tiny strands of different chemicals found in the cells of living things. DNA is kind of like the computer code for a living thing’s body. It tells each cell what to be when it grows up as well as what to do on a daily basis to stay alive.

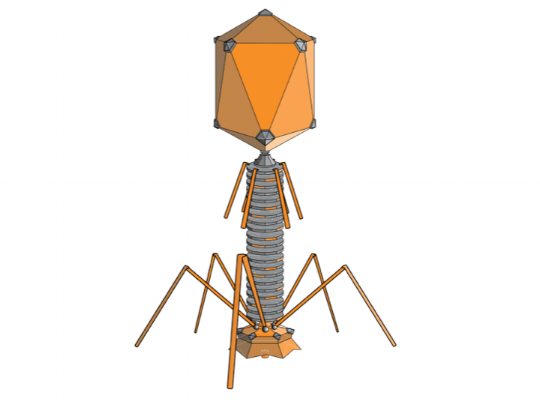

Viruses also have DNA, except most of the time the DNA doesn’t do anything. A virus doesn’t have a metabolism and it doesn’t grow or change, so it doesn’t need DNA to tell it how to do either of those things. Despite the fact that some viruses look like cool robot spiders from outer space, viruses can’t move on their own, so the DNA is not there for that.

The DNA just sits in the virus’s protein case, possibly forever.

But many times, not forever. Even though viruses can’t reproduce on their own, they really want to reproduce themselves. They can only do this when they get carried to or bump into the cell of whichever living thing they are built for. Once that happens the virus attaches to the cell and then it dumps its DNA into the cell. The DNA goes into action by taking over the cell. It commands the cell to create more viruses. The cell makes and releases a bunch of copies of the virus. All those new viruses may then invade other nearby cells, take them over, and make them make even more virus copies. And so the infection spreads.

The fact that viruses reproduce themselves, even though they can’t do it on their own, is another thing that puts them into a living thing/nonliving thing gray area.

These, and some other more complicated similarities, make some scientists think that viruses should be considered living things. These scientists aren’t saying viruses are eating, drinking, and growing. They’re not the Flat Earthers of biologists. They’re saying that maybe we need to redefine what makes something a living thing. The more we explore nature, the more we are discovering how diverse it is and how it does not all fit into the neat little categories we keep hoping will describe everything. But that’s part of the fun too. Even in the 21st Century, the universe still regularly takes us by surprise.

To learn more about the differences between living things and nonliving things and the diversity of nature, read my book Living Things and Nonliving Things. To learn more about microbes, read my book Where Wild Microbes Grow.

Online references and resources

Arizona State University. Ask A Biologist: Are viruses alive?

https://askabiologist.asu.edu/questions/are-viruses-alive

Santa Barbara Independent. "Viruses, Part I: Origins"

https://www.independent.com/news/2010/oct/02/viruses-part-i-origins/

Scientific American. "Are Viruses Alive?"

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-viruses-alive-2004/

University of California, Santa Barbara. ScienceLine How is it that viruses are not living things?

http://scienceline.ucsb.edu/getkey.php?key=3316

Also this:

The Vital Question: Why is Life the Way It is? by Nick Lane

Photos and Images

Click the photos and images used above to find their sources.