For the most part, getting hypothermia is not something you should include on your bucket list. Hypothermia, or having your body temperature drop below 95 degrees Fahrenheit, can result in symptoms ranging from mental confusion, such as a desire to take all your clothes off in freezing temperatures (I am not making that up), to the world’s worst symptom, death. So it’s not great, but long ago on a battlefield far, far away (well, far away as long as you don’t you live near Shiloh, Tennessee), getting hypothermia may once have saved some Civil War soldiers’ lives.

As you may or may not remember from my last post, in 1862 some Civil War soldiers had glowing wounds. It is thought that tiny worms that live in the soil moved into the wounds and brought bioluminescent bacteria with them. The glowing bacteria released toxins in the soldiers’ wounds that killed other invading bacteria and helped prevent the wounds from becoming infected. Here's a mildly disturbing graphic that shows their standard process:

We know how these nematodes and bacteria may have saved the soldiers' lives because two teenagers around the year 2000 resisted the urge to spend all their time listening to Limp Bizkit albums, and instead decided to use some of their teenage years using science to figure out what made those Civil War soldiers glow. They came up with convincing evidence that it was the glowing bacteria described above (or for more details, see my last post). But there was one problem with their theory. These bacteria cannot live in warm temperatures, and the human body tends to be pretty warm.

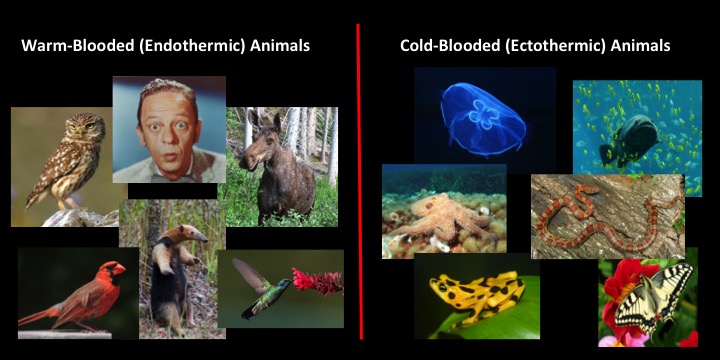

If you have ever had a thermometer in your mouth, then you probably know that the inside of the human body is supposed to be around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. I am willing to bet that, right now as you read this, the air around you is not 98.6 degrees (unless you enjoy spending hot, humid summer days sitting outside reading blog posts about the relationship between microbes and hypothermia). Your body temperature can be much warmer than the air around you, because you are warm-blooded. “Warm-blooded” does not mean your blood is the only warm part of your body. Every part of your body is warm (which is why scientists like us to say “endothermic” instead of “warm-blooded”). Endothermic animals (like you) are able to take energy from the food they eat and use it to heat their entire bodies. This allows them to survive in colder climates and be active in much colder temperatures than cold-blooded (ectothermic) animals, like reptiles, are able to do.

Your body makes its own heat, but if you spend too much time walking around in shorts and t-shirts in the middle of winter, then all the heat in your body can escape and your body temperature will drop, possibly leading to hypothermia. This is almost always a bad thing, unless you are a wounded Civil War soldier lying in the dirt after the Battle of Shiloh.

The Battle of Shiloh happened on April 6-7, 1862. April 6 is only about two weeks after the first day of spring, which means it’s only about two weeks after winter, which means it can get pretty cold at that time, even in the South. Many soldiers on both sides of the battlefield wrote accounts that a big cold front came through in the middle of the battle. The cold front brought torrential rains and cold temperatures, meaning any wounded soldier who could not drag himself off the battleground, spent a couple days being cold and wet and lying in the mud.

As much as I don’t recommend you spend a couple days being cold and wet and lying in the mud, that set of circumstances probably saved some of the soldiers’ lives. The coldness and wetness lowered the soldiers’ body temperatures to the point that many of them probably had hypothermia. This made their bodies cool enough to make them a suitable habitat for the glowing bacteria. When the nematodes moved into the wounds and dropped off their bacteria buddies, the bacteria were able to live in the cool wounds and release their other-bacteria-killing toxins that saved the soldiers’ wounds from becoming infected.

The high school students Bill Martin and Jon Curtis figured this out. Because they did such a good job of using science to solve this 140-year old mystery, they won the 2001 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair with this project.

To learn more about bacteria and other microbes, read my free eBook Where Wild Microbes Grow.

To learn more about the process of science, read my free eBook Uncovering Earth’s Secrets.

Online References and Resources:

AAAS ScienceNetLinks. "Glowing Wounds."

http://sciencenetlinks.com/science-news/science-updates/glowing-wounds/

Mental Floss. "Why Some Civil War Soldiers Glowed in the Dark." Article by Matt Soniak.

http://mentalfloss.com/article/30380/why-some-civil-war-soldiers-glowed-

dark#ixzz2MI9x9Ovm

Microbe Wiki. "Photorhabdus luminescens."

https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Photorhabdus_luminescens

The National Center for Biotechnology Information. "The lumicins: novel bacteriocins from Photorhabdus luminescens with similarity to the uropathogenic-specific protein (USP) from uropathogenic Escherichia coli."

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12351238

USDA. "Students May Have Answer for Faster-Healing Civil War Wounds that Glowed."

http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2001/010529.htm

Photos and Images:

Click the photos and images used above to find their sources.